Uncertainty Estimation through HyperNetworks

Introduction

Neural Networks have through the past decade shown superiour performance in supervised tasks such as Computer Vision and Speech Recognition. However, in the past few years, the field of Deep Learning has moved away from solving tasks which can simply be set up as a supervised problem to exploring if Neural Networks can be used for solving more meta related tasks. This can be tasks such as using a neural net to optimize another neural network 1, training neural networks to learn more efficiently over a large set of different tasks 2 or even using a model to explain any other models predictions. 3

Since Neural Networks seem to be able to model any function due to the universal approximation theorem, it would be interesting to see if they can model Neural Networks themselves. To put it in another way, could one use a neural network to generate another neural network which in turn solves som predefined task? For example, having a neural network output the weights of a network which solves a classification task.

There are several benefits to this. One could for example generate large ensembles of networks by only training a single, generating network or gain insight into the distribution of neural networks by effeciently being able to sample them. These type of networks have been studied before and were denoted HyperNetworks by Ha et al. 4

One subfield where the benefits of Hyper Networks could prove most fruitful is within Uncertainty Estimation. This is the angle this blog post will take when exploring HyperNetworks.

Uncertainty Estimation

One way of estimating the uncertainty of a Neural Network is to use Ensemble Methods. Lakshminarayanan et al. 5 approach the problem by training an ensemble of $M$ networks and averaging the results. The divergence between the performance of the networks is then interpreted as the level of uncertainty the network has in its predictions. There are two problems with this approach. The first is the computation required to train $M$ networks, even though this could be done in parallel. The second is how different the networks you train really are. Estimating the true uncertainty only works given that you are sampling i.i.d networks from the distribution of networks which achieve a certain performance threshold. The networks have different initial conditions and are trained on different random shufflings of the data. This does not however guarantee that they will converge to different solutions.

As we will see in this post, these two issues can mitigated by the use of HyperNetworks.

Hypernetworks are networks whose output is the parameters of another network, denoted the main network. One of the first to explore this was Schmidhuber 6 who similarly to Ha et Al. 4 explores a dual net setup by considering using a weight-generating network and a ‘fast-weight’ main network in sequential tasks. The benefit of this is that the fast-weight network serves as short-term memory, always changing for every input in the sequence while the hypernetwork acts as a memory controller.

From Schmidhubers initial approach followed a number of derivations of the same idea has been found in Meta Learning 7 and Generative models 8 amongst others.

HyperNetworks have previously been explored for uncertainty estimation by Ratzlaff. et al 9. This post will explore their approach and extend it to further generate more diverse networks.

Method

Consider the distribution of targets given the input

In practice, it is very hard to sample from the posterior of the parameters, $p(\theta|x)$. Approximations such as variational inference or ensemble methods are usually used instead 5 10.

However, sampling from a complex distributions is an area where deep neural networks thrive. VAEs and GANs have been shown to generate images that are almost indistinguishable from real-life. There are a number of differences between how these two models operate. Normally these two models are trained in an unsupervised fashion using samples from the true target distribution. In our case we do not know the true target distribution, nor do we have any samples from it to train on. The key aspect we will make use of is that to train a GAN to generate samples, one only needs an accurate discriminator who can judge if a sample is good or not. In the case of images for example, the discriminator is a binary-classifier trained alongside the generator to assign a score to each generated sample, determining if its from the true distribution or not.

In our case the discriminator is the performance of the a neural network on some classification/regression task. We generate the weights for this main network using a generator network on samples $x \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)$. During inference time, we can now generate hundreds of networks by a single forward pass of our generator. Given that these are sufficiently different from each other, we can get a measure of model uncertainty by measuring the difference in performance of these networks.

Generating diverse networks

The problem with this approach is that there is nothing stopping the generated networks to be very similar to eachother. This is analogous to the mode-collapse problem seen in GANs where for example images from only one class are generated. We will try two approaches to mitigate this.

The first is an approach used by in the original HyperGAN paper 9. The generator generates weights and biases of the main network using two output layers on a shared, final layer. This final layer is denoted the mixer layer. The output of the mixer layer is simultaneously fed to a discriminator network which classifies if the output belongs to a high-entropy distribution such as the uniform distribution. In this way, the mixer layer is trained to generate diverse outputs which, when used by the final outputs layers would possibly generate a diverse sets of weights.

Diverse networks using mutual information

To prevent mode collapse in Generative Adversarial Networks, Belghazi et. al 11 regularize the GAN objective with the mutual information between the prior samples and the generated data. The objective for the generator then becomes

Here, $z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)$ is the prior noise and $\beta$ is a hyperparameter controlling the level of regularization.

By ensuring that the generated samples share a high mutual information with the input, we can force the generator to generate diverse samples.

Training details

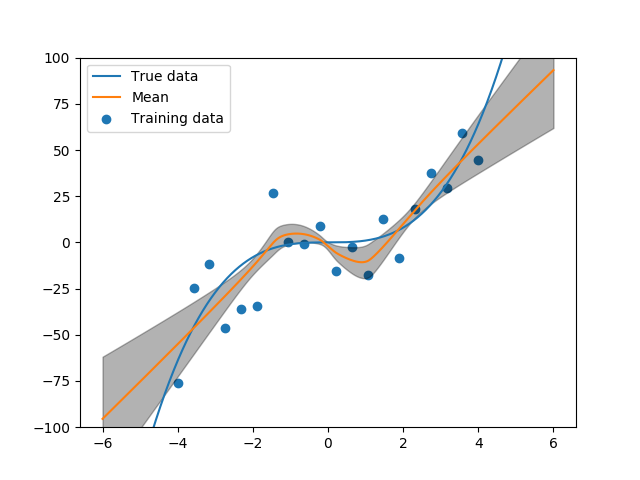

After training such a model, one can sample any number of networks from it and perform inference. We train a HyperGAN on a toy dataset of 20 datapoints sampled from

We then sample $1000$ networks and calculate the mean and standard deviation of the combined inferences. The figure below illustrates the results.

As is seen in the figure, when there are more points, the network is more certain in its predictions. As we further away from the mass of samples, we see a clear deviation between our networks predictions, illustrating the data uncertainty.

We train the networks by sampling a batch of samples from the prior $Z$. From this we generate a batch of weights and biases corresponding to the layers in our main network. We update the main networks weights and perform inference for each batch in the training data. We average over the loss of each generated network and perform a backward pass. We thus generate a set of networks, perform a full epoch of training and then generate a new set of networks. The weight_batch parameter determines the number of networks we sample. Sampling more networks allows the network to optimize for a greater number of prior samples, thus each sampled network during inference time will already be a good fit.

Results

We evaluate our HyperNetwork with respect to both the objective function and uncertainty estimation. To evaluate the uncertainty we follow that of Ratzlaff et al. [6] and measure the relative standard deviation of the weights as well as visualizing the divergence in predictions in the ensemble.

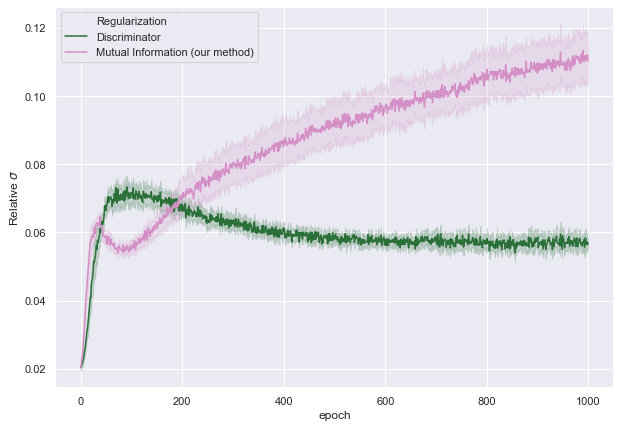

In the figure, below we evalaute the relative standard deviation of the $\mathcal{L}_2$-norm of the weight-matrices.

From the above figure one can note that regularizing the mixer output to share a high mutual information with the input noise, one can achieve successively greater dispersion among the inferred models. This points to two important properties of our method; First that we can possibly find a larger set of models which give a sufficiently nice solution and secondly that the longer we train, the more divergence between the trained models we can acheive.

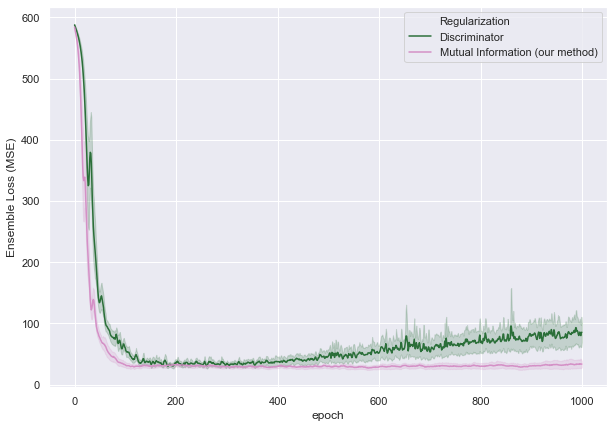

The increased diversity of the generated networks is also apparent in the performance of the networks.

From Figure 4 it is apparent that as the training proceeds, the network regularized with a Discriminator eventually overfits while networks regularized with mutual information exhibit both a stable and lower loss. A more diverse ensemble makes it more robust to the test data.

Classification

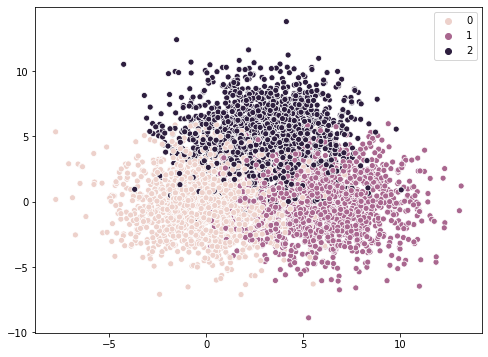

We can also use our approach on a simple classification task.

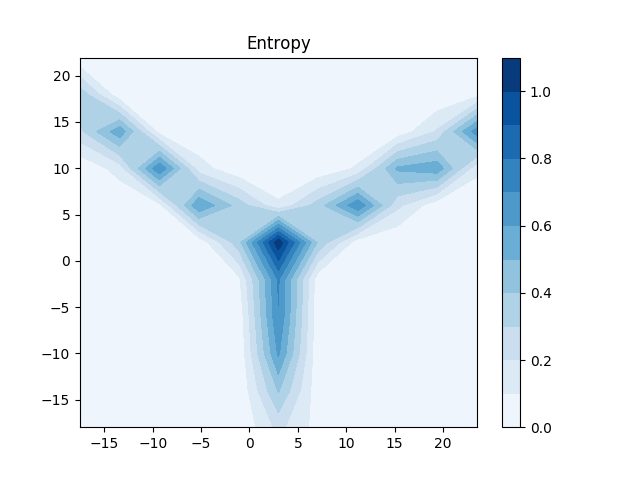

. We draw samples from three gaussians with overlapping distributions. This way we generate a dataset of three different classes with an uncertain decision boundary. We train a Hypernetwork to estimate the probability of a sample belonging to a certain class and calculate the average of this probability over a generated ensemble of networks. We then proceed to calculate the Entropy over the class probabilities to get a measure of uncertainty

We evaluate the entropy on a grid of points covering the sample space.

.

From comparing Figure 5 and 6, we note that in the decision boundary we get an almost maximum entropy showing the uncertainty of the classifier in these points. Note that on out-of-distribution samples, the classifier shows a high certainty in its predictions. Thus, we cannot give any insight into out-of-ditribution samples in this example using our method.

Conclusion and further work

HyperNetworks are interesting because they push the use of neural networks from supervised learning more meta tasks which ultimately relate to understanding neural networks themselves. Uncertainty estimation is of ever-growing importance, not only in fields where it is critical to be able to trust the models decisions such as in automous vehicles or healthcare but also in exploration in Deep Reinforcement Learning 12. Recently, HyperNetworks have been proposed as a method to efficiently estimate uncertainty in Deep RL 13.

There is thus a growing need to estimate uncertainty, but also to understand neural networks in general. Being able to effeciently sample diverse and performant network can yields insights into the properties of these networks. As HyperGANs were inspired by GAN literature, perhaps methods of deriving interpretable latent representation of networks is possible, similarly to how GANs can combine images of different properties by interpolating in the latent space.

It would also be interesting to efficiently explore the loss surface of Neural Networks. Given that we can sample a set of diverse, performant networks, we can interpolate between them and thus achieve paths in the loss surface between two local minimas. This could possibly reveal the shape of the loss surface.

References

-

https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.04474 “Learning to learn by gradient descent by gradient descent” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.03548.pdf “Meta-Learning: A Survey” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1602.04938.pdf “‘Why Should I Trust You?’ Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.09106.pdf HyperNetworks ↩ ↩2

-

https://deepmind.com/research/publications/ simple-and-scalable-predictive-uncertainty-estimation-using-deep-ensembles “Simple and Scalable Predictive Uncertainty Estimation using Deep Ensembles” ↩ ↩2

-

ftp://ftp.idsia.ch/pub/juergen/fastweights.pdf “Learning to Control Fast-Weight Memories: An Alternative to Dynamic Recurrent Networks” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1703.00837.pdf “Meta Networks” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.00779 “Neural Autoregressive Flows” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.11058.pdf “HyperGAN: A Generative Model for Diverse, Performant Neural Networks” ↩ ↩2

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1505.05424.pdf “Weight Uncertainty in Neural Networks” ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.04062 “MINE: Mutual Information Neural Estimation” ↩

-

https://papers.nips.cc/paper/8080-randomized-prior-functions-for-deep-reinforcement-learning.pdf “Randomized Prior Functions for Deep Reinforcement Learning” ↩

-

https://openreview.net/pdf?id=ryx6WgStPB “HyperModels for Exploration” ↩